418

Views & Citations10

Likes & Shares

CASE REPORT

A 36-year-old Gavida 3 para 1 (1 alive) woman was referred to the antennal clinic of our hospital at a gestational age of 36 weeks and 3 days on account of ultrasound diagnosis of major degree placenta previa and transverse lie. The last delivery was via spontaneous vaginal delivery of a live male neonate, birth weight of 3.8 kg. No history of previous uterine surgery. Had history of prior first trimester spontaneous miscarriage that was managed at home.

On examination, she was not pale, afebrile anicteric and not dehydrated. The respiratory and cardiovascular systems were essentially normal. Abdominal examination revealed a gravid uterus, symphysio fundal height was 36 cm. A single fetus in transverse lie. No palpable contractions and fetal heart rate of 146 beats per minute. Inspection of the vagina showed no vaginal bleeding. Digital examination was not done. Repeat ultrasound at the clinic showed a live singleton fetus in transverse lie with estimated fetal weight of 3.2 kg. Placenta was type IV placenta previa. Doppler scanning was not done. Other parameters were essentially normal. A diagnosis of major degree placenta previa was made and patient was admitted in prenatal ward for elective caesarean delivery at 37 weeks.

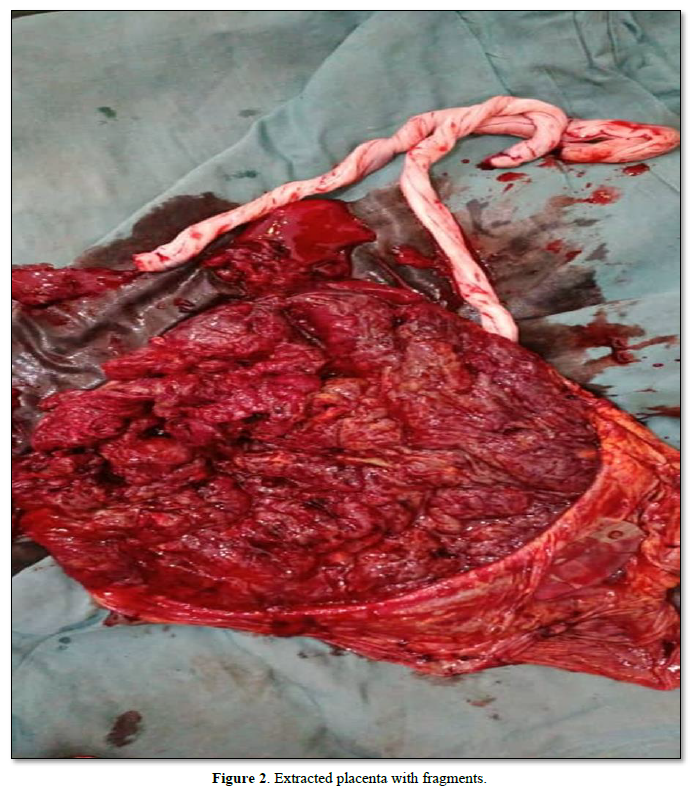

Four units of blood were grouped and crosshatched for her. Full blood count, serum electrolyte, urea and creatinine and clothing profile done were essentially normal. Elective Caesarean section was done under general anesthesia. Intra operative finding include clean pelvis, tortuous vessels noted at the lower uterine segment. A lower segment uterine incision was made and the placenta was side stepped. A live female neonate weighing 3. 25 kg with good Apgar’s score was delivered. Attempt to spontaneously extract the placenta failed as it was morbidly adherent. The placenta was manually extracted with minimal force (extirpative technique), some segments coming out in piecemeal (Figure 2). There was associated profuse bleeding. Hemostatic sutures were placed at the bleeding points in the placental bed using vicryl 2 sutures. Further endouterine square sutures penetrating to the myometrium were placed at the placental bed anteriorly and posteriorly. Both uterine arteries were subsequently ligated with vicryl 2 sutures. Uterotonics were given. Haemostasias was completely achieved. The uterus and abdomen were closed using conventional technique. Estimated blood loss was 1.5 l. She was transfused with 2 units of blood intra-operatively. Her packed cell volume was 28% and she was transfused another 2 units of blood postoperatively. Her recovery was uneventful and patient was discharged on the fifth day after surgery and in good condition.

DISCUSSION

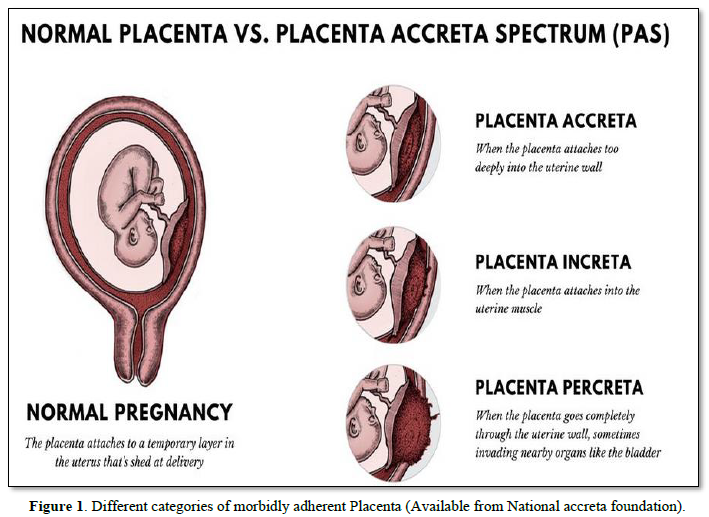

It has been thought that total or partial absence of the ‘decidua basalis’ is responsible for the occurrence of placenta accrete [7]. Caesarean section often leads to failure of reconstitution of the decidua basalis [8]. The major risk factor for placenta accreta is placenta previa and previous uterine surgeries. In parturient with placenta previa, there is 10% increased risk of placenta accreta if they have had one caesarean section but this risk increases to 60% if they have had more than four caesarean deliveries [9]. However, for women who do not have placenta previa, there is less than 1% increase risk of placenta accreta after one caesarean section and this remains same for up to four caesarean sections [9]. Other risk factors for placenta accreta include multiparity, age greater than 35 years, submucous fibroid, and endometrial lesion [9,10]. Our patient had major degree placenta previa and was about 36 years of age and therefore had significant risk factors for placenta accreta.

Imaging studies (color flow Doppler ultrasonography) during antenatal is valuable and need to be performed in all pregnant women who have placenta previa or who are at risk of developing placenta accreta [1]. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is beneficial in determining the level of infiltration in morbidly adherent cases but the final diagnosis of the type of adherent placenta is made histologically or intraoperatively [1]. In centers where there is no Doppler ultrasound and MRI facilities as found in some poor resource settings, antenatal diagnosis before delivery would not be possible. Diagnosis in such setting is frequently made intraoperatively or intrapartum. Though our patient had ultrasound done (not Doppler) to assess fetal viability and wellbeing during the third trimester scanning, diagnosis of placenta previa was sufficient enough for the caesarean section which was electively done for her. Nonetheless, if the diagnosis of placenta accreta was made prior to surgery, additional preparations would have been made in terms of surgical team members, blood and blood products and timing of surgery.

Surgical management options for placenta accreta include ‘caesarean hysterectomy’, ‘extirpative method’, ‘conservative treatment’ and ‘alternative conservative approach’ (one step conservative surgery) [11]. Caesarean hysterectomy is presently considered as the reference management standard for placenta accreta and is currently recommended by various bodies and [12-14] is associated with less maternal morbidities and mortalities. However, this approach has a major disadvantage of loss of fertility. The extirpative method involves forceful manual extraction of the placenta in a bid to have an empty uterus. This method is associated with a greater risk of severe hemorrhage and possibly peripartum removal of the uterus than conservative method [15,16]. However, the extirpative method unfortunately happens in cases of placenta accreta that is undiagnosed before surgery as occurred in our patient. The approach is as a result of unexpected intraoperative complication (bleeding) of unsuspected placenta accreta, but conserves fertility if successfully done along with other manoeuvres. Diagnosis of placenta accreta was not made preoperatively in our patient who was also desirous of more children. The placenta was manually removed with application of minimal force leading to removal of placental fragments that retained. Hemostatic sutures were placed at bleeding points. Endouterine square sutures were placed at the placenta bed and both uterine arteries were ligated. Tranexemic acid injection was used prophylactically. Hemostasis was secured, uterine contraction achieved and maintained with uterotonics. Other conservative techniques and manoeuvres include prior transfemoral or trans humeral catheterization of descending aorta, use of external uterine compression sutures (B-Lynch), use of Bakri balloon for intrauterine packing, embolization of uterine arteries [17-19], however this equipment and skills may not be readily available in poor resource settings even when placenta previa accreta is diagnosed before planned delivery.

CONCLUSION

It is very essential to do a Doppler ultrasonography imaging in women who are at higher risk of developing morbidly adherent placenta (placenta previa, advanced maternal age and previous uterine surgeries). Conservative approach with preservation of the uterus could be taken into consideration as safe approach in a well selected cases of placenta accreta especially in patients who have not completed their family size. However, patients need to be adequately counselled on the associated complications.

- Women’s Health Service (2019) Placenta Previa and Placenta Accreta. Available online at: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://edu.cdhb.health.nz/Hospitals-Services/Health-Professionals/maternity-care-guidelines/Documents/GLM0002-Placenta-Praevia-Placenta-Accreta.pdf

- Oyelese Y, Smulian JC (2006) Placenta previa, placenta accreta, and Vasa previa. Obstet Gynecol 108(3): 694.

- Quinlivan WLG (1961) Placenta Previa Accreta. JAMA 176(12): 1035-1036.

- Canonico S, Arduini M, Epicoco G, Luzi G, Arena S, et al. (2013) Placenta previa percreta: A case report of successful management via conservative surgery. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2013: 702067.

- ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice (2002) ACOG Committee opinion. Number 266, January 2002: Placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol 99(1): 169-170.

- Comstock CH (2005) Antenatal diagnosis of placenta accreta: A review: Antenatal diagnosis of placenta accreta. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 26(1): 89-96.

- Dahiya P, Nayar KD, Gulati JS, Dahiya A (2012) Placenta Accreta Causing Uterine Rupture in Second Trimester of Pregnancy after in vitro Fertilization; A Case Report. J Reprod Infertil 13(1): 61-63.

- Benirschke K, Kaufmann P (2002) The Pathology of the Human Placenta - 4th New York: Springer.

- Mogos MF, Salemi JL, Ashley M, Whiteman VE, Salihu HM (2016) Recent trends in placenta accreta in the United States and its impact on maternal-fetal morbidity and healthcare-associated costs, 1998-2011. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 29(7): 1077-1082.

- LeMaire WJ, Louisy C, Dalessandri K, Muschenheim FM (2001) Placenta percreta with spontaneous rupture of an unscarred uterus in the second trimester. Obstet Gynecol [Internet]. 98(5 Pt 2): 927-929.

- Sentilhes L, Kayem G (2013) Management of placenta accreta. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 92: 1125-1113.

- Seng JJ, Chou MM, Hsiehb YT, Wene MC, Hob ES (2006) Differential expression of vascular endothelial growth factor, placenta growth factor and their receptors in placentae from pregnancies complicated by placenta accreta. Placenta 27: 70-78.

- Clark SL, Belfort MA, Dildy GA, Herbst MA, Meyers JA, et al. (2008) Maternal death in the 21st century: Causes, prevention, and relationship to cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 199: e36-e37.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Belfort MA (2010) Placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol 203: 430-439.

- Kayem G, Davy C, Goffinet F, Thomas C, Clement D, et al. (2004) Conservative versus extirpative management in cases of placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol 104: 531-536.

- Bretelle F, Courbiere B, Mazouni C, Agostini A, Boubli L (2007) Management of placenta accreta: Morbidity and outcome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 133: 34-39.

- Nelson WL, Obrien JM (2007) The uterine sandwich for persistent uterine atony: Combining the B-Lynch compression suture and an intrauterine Bakri balloon. Am J Obstet Gynecol 196(5): e9-e10.

- Cheng YY, Hwang JI, Hung SW (2003) Angiographic embolization for emergent and prophylactic management of obstetric hemorrhage: A four-year experience. J Chin Med Assoc 66(12): 727-734.

- Flood KM, Said S, Geary M, Robson M, Fitzpatrick C, et al. (200) Changing trends in peripartum hysterectomy over the last 4 decades. Am J Obstet Gynecol 200(6): 632.e1-6.

QUICK LINKS

- SUBMIT MANUSCRIPT

- RECOMMEND THE JOURNAL

-

SUBSCRIBE FOR ALERTS

RELATED JOURNALS

- International Journal of Medical and Clinical Imaging (ISSN:2573-1084)

- Journal of Otolaryngology and Neurotology Research(ISSN:2641-6956)

- Advance Research on Endocrinology and Metabolism (ISSN: 2689-8209)

- Journal of Psychiatry and Psychology Research (ISSN:2640-6136)

- Journal of Ageing and Restorative Medicine (ISSN:2637-7403)

- Advance Research on Alzheimers and Parkinsons Disease

- International Journal of Diabetes (ISSN: 2644-3031)